Desire in a Leaky Jar: Wants and Needs in Classical Greek Philosophy

|

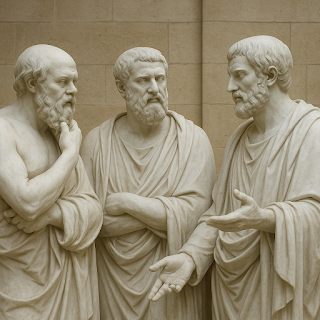

| AI art |

Introduction

In today’s consumer-driven society, where the market seems to manufacture desires as rapidly as it satisfies them, the distinction between what we need and what we desire has become increasingly elusive. Yet this is not a new dilemma. Classical Greek philosophers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—devoted careful thought to the nature of human wants, drawing a sharp ethical and philosophical boundary between finite needs and infinite desires. This article examines how each of these thinkers approached the problem, exploring their metaphors, arguments, and distinctions, and how their insights might still illuminate our lives today.

Socrates and the Leaky Jar of Insatiable Desire

In Plato’s Gorgias, Socrates delivers one of the most vivid critiques of unrestrained desire through a memorable analogy. He compares the undisciplined soul to a jar riddled with holes, forever leaking whatever is poured into it. This image is offered during a debate with Callicles, who defends a life of indulgence as natural and fulfilling. Socrates counters:

“They pour into leaky jars, but they can never be filled.” (Gorgias 493d)¹

This metaphor casts unregulated epithymia—the Greek word for desire or appetite—as inherently futile. The person who lives to satisfy every urge is condemned to endless labor, like Sisyphus pushing his rock. For Socrates, such a life lacks order, direction, and ultimately satisfaction. In this dialogue, his contrast between the overflowing, chaotic life of the desiring man and the measured, temperate life of the philosopher implies a hierarchy: some wants (perhaps those necessary for survival and moderation) can be fulfilled and left behind, while others are inherently insatiable.

Plato’s Tripartite Soul and the Moral Hierarchy of Desire

Plato takes Socrates’ insight further in the Republic, where he elaborates a detailed psychology of the human soul. He distinguishes three parts: reason (logos), spirit (thymos), and appetite (epithymia)². In a just soul, reason governs the other parts, particularly desire, which Plato sees as the source of internal disorder when left unchecked.

He introduces a crucial distinction between necessary and unnecessary desires. Necessary desires are tied to health and basic functioning—such as hunger or the need for shelter. Unnecessary desires, by contrast, are those that go beyond natural limits, such as the craving for luxury, fame, or excess wealth:

“We must consider whether desires are necessary or not. There are some we can’t get rid of and others we can.” (Republic 558d)³

This moral distinction is reflected in Plato’s political philosophy as well. In Book II of the Republic, he constructs an ideal “healthy” city based on the satisfaction of needs (chreia), where citizens live simply and cooperatively. However, once the city succumbs to the pursuit of luxury—symbolic of unchecked desire—it requires expansion, war, and ultimately injustice. The implication is clear: justice, both individual and social, depends on the rational containment of desire within the bounds of need.

Aristotle’s Ethical Naturalism—Needs, Desires, and Rational Choice

Aristotle, Plato’s student, shares the concern with distinguishing natural needs from unnecessary desires, but he frames it in more biological and ethical terms. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he considers the good life as one in which human beings realize their function (ergon) through the cultivation of virtue and rational activity⁴. Desires are not inherently bad, but they must be moderated according to reason.

While he doesn’t deploy the metaphor of the leaky jar, Aristotle is equally skeptical of lives guided by unbounded wanting. He makes an explicit distinction between desires rooted in nature and those created by convention or habit. In Politics, he distinguishes between natural wealth-getting, which aims to satisfy genuine needs (food, shelter, tools), and unnatural chrematistics—the endless accumulation of wealth as an end in itself:

“Desire is unlimited, and the majority live for its satisfaction… but the use of wealth must have a limit.” (Politics I.9, 1257b)⁵

Here, we see an early critique of proto-capitalist accumulation: the natural economy supports life; the unnatural economy enslaves it to desire. Aristotle's vision of eudaimonia—human flourishing—is incompatible with the bottomless pit of artificial wants. It is achieved instead through rational self-regulation, satisfying those needs conducive to virtue.

Conclusion: Why This Distinction Still Matters

For Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the line between need and desire is more than semantic, it is a foundational ethical distinction. To pursue desires without reflection is to live like the leaky jar: always full of effort, never full of meaning. To live well is to cultivate the wisdom to discern the difference.

In a world where advertising and social media constantly amplify desires, their insights are not merely historical curiosities. They provide conceptual tools for navigating the overstimulated emotional economy of modern life. As consumer culture encourages limitless wanting, the classical ideal of self-limitation offers a radical—and liberating—alternative. Perhaps now more than ever, we should ask: Is this a need, or merely a desire echoing in an empty jar?

References and Notes

- Plato, Gorgias, 493d.

- Plato, Republic, Book IV.

- Plato, Republic, 558d–559c.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, esp. Book VII.

- Aristotle, Politics, Book I, especially 1257a–1258a.

Comments

Post a Comment